The daughter of France’s sauciest couple has always struggled with the glare of publicity. As Charlotte Gainsbourg releases her most confessional album, she tells Elizabeth Day about her wild childhood and, for the first time, how she still struggles with the untimely death of her sister.

JAMES ANDANSON/GETTY

By The Sunday Times, November 12 2017

When Charlotte Gainsbourg was seven or eight, her mother came to pick her up from school. She remembers this day in particular because her mother was wearing a skintight blue sequined dress.

“She was so glamorous, so beautiful,” Gainsbourg says now, sitting on the terrace of her Paris home in the dappled sunlight of the 7th arrondissement. Even today, some 40 years after the event, there is a note of wonderment in her voice. “She was …” Gainsbourg pauses to think of the right word, “… serene.”

It’s an appropriate reaction when one’s mother is the English actress and singer Jane Birkin — a woman so stylish, she went on to have a bag named after her by Hermès. The dress was a dazzlingly impractical thing to wear on the school run, which served only to heighten the magic.

“You could see her whole body shape. It was very clingy and I remember her hips and I just …” Gainsbourg mimes hugging her mother close to her and burying her head in the dress. Her movements are quick and sprightly, and she looks much younger than her 46 years.

Gainsbourg is not a blue sequin type of person and admits she doesn’t even own a Birkin handbag (“I wouldn’t use it!”). Today, she is dressed in exactly the sort of understated cool attire one would expect from a gamine French rock star: white trainers, black jeans and a black T-shirt hanging from her slender frame. Her look is androgynous, save for the small diamond heart hanging on a chain around her neck. Her hands, when she gestures, are unexpectedly big and workmanlike. She is a compelling mixture of the feminine and the masculine.

Gainsbourg at 46, the same age as Kate when she died

EMMANUEL FRADIN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

Her father was Serge Gainsbourg, the celebrated French singer who recorded Je t’aime … moi non plus with Birkin in 1969 — a song so sulphurously sexual that it was denounced by the Pope and banned by the BBC. After his death from a heart attack in 1991, at the age of only 62, Serge was described by President François Mitterrand as “our Baudelaire, our Apollinaire”.

That’s quite a reputation to live up to and, for much of her adult life, Gainsbourg has been defined by her childhood. She combines both her parents’ talents and is a critically acclaimed singer and actress who has starred in more than 50 films and is renowned for her stellar turn in Lars von Trier’s experimental horror film Antichrist, which won her the best actress award at Cannes in 2009. Despite releasing four well-received albums (including one she recorded at the age of 15, with music written by her father), though, she was so intimidated by Serge’s reputation that she never wrote her own lyrics. Until now.

Her new album, Rest, is more personal than her previous work, and Gainsbourg sings in both French and English about her love for her father, her battles with stage fright and the sudden death, in 2013, of her older half-sister, Kate, Birkin’s daughter from her first marriage to the film composer John Barry. Kate fell from the fourth-floor window of her Paris flat on a Wednesday evening two weeks before Christmas. She was 46, a photographer who had spent many years battling drug and alcohol addiction.

“We still don’t know if it was an accident for sure,” Gainsbourg says in fluent, accented English. “It’s such a violent death that it doesn’t make sense. Nobody knows. So, one day I think it’s a real [conscious] act, and the next day I’ll think it’s an accident. I want to believe it’s an accident.”

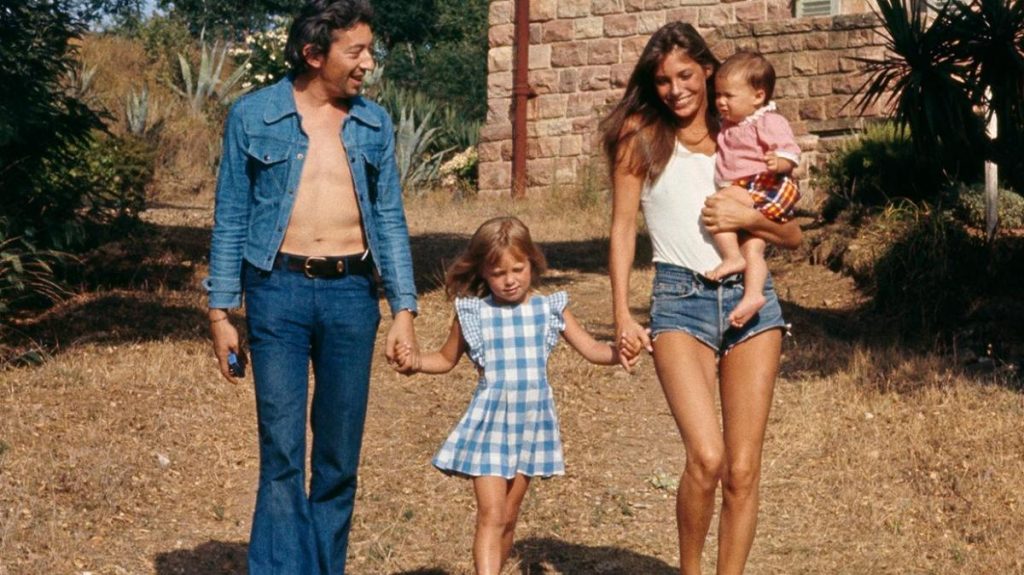

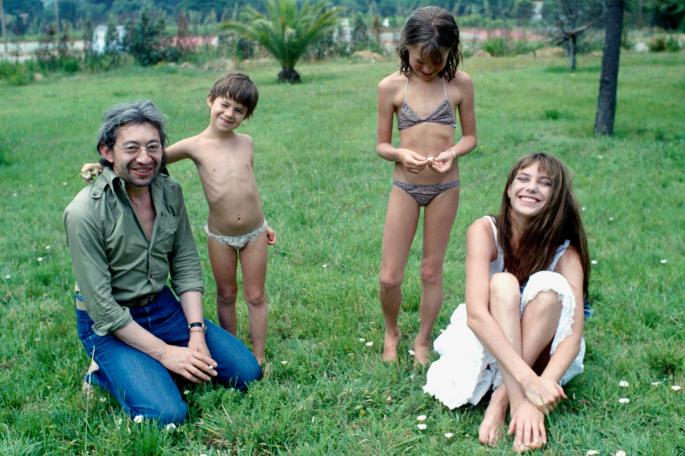

Field of dreams: Charlotte, second from left, has happy memories of family holidays with her sister Kate. Photo GETTY

She shakes her head, breaks off and pours us some sencha green tea, served from a tiny hand-painted pot. During the course of our conversation, the pot is occasionally refilled with water from the kettle, which Gainsbourg has brought out onto the terrace from the kitchen, an act that seems both slightly eccentric and perfectly practical.

One of the songs on the album, entitled simply Kate, refers to her sister as having “a soul too tender that nothing soothed”. “She was an exceptional person,” Gainsbourg explains. “You realise that, of course, when that person is not there any more. Not that I didn’t know before, but there was no urgency to make it clear.”

When Kate died, “our whole family collapsed”, Gainsbourg explains. Her mother “was gone for years. Really gone. She was not there. I mean, she wouldn’t get up. If you told her to come over, she would, but she didn’t talk, not to my children or to anyone.”

In 2014, Gainsbourg moved to New York with her three children (Ben, 20, Alice, 15, and Jo, 6) and her longtime partner, the French-Israeli actor and director Yvan Attal. It was a self-imposed act of exile. She needed to get away from Paris, where she felt suffocated by everyone knowing who she was and what had happened.

“And once I was in New York, I got going,” she says. “I wrote [song lyrics] and I didn’t care if it was good or bad. The fact that I was not being recognised in the streets — just stepping into a new life — it helped.”

Playing her part: Gainsbourg (left) in her first film role as Catherine Deneuve’s daughter in Paroles et musique – COLLECTION CHRISTOPHEL

When her father died, “the whole country was talking about him. It was a national grief and people would talk about their sorrow to me. Sometimes it was so disturbing, to share that suffering. I was 19, but I felt very young. I closed myself completely and I wouldn’t talk about him.”

For a long time, hearing his songs on the radio — in the back of taxis or at restaurant tables — would cause a pain so acute, she had to ask for the music to be turned off. She kept his house on Rue de Verneuil, the home in which she had lived as a child with Kate, just as he had left it.

“It was like a mausoleum and I became like Miss Havisham,” she says. “But that’s the way I needed to keep it. I couldn’t go to his grave because that was public. People were there all the time.”

Rest also includes a song about her father’s grave, in the Montparnasse cemetery. “The coffin bolts,” she sings over synth-heavy electro-pop reminiscent of 1970s horror soundtracks, “where goes my kiss, my heart laid bare without you.”

It sounds more like something you’d say about a lover than a father, but their relationship has always been a slightly uneasy mix of filial closeness and romantic intensity. In 1984, when Gainsbourg was 13, she sang with Serge on a single called Lemon Incest, which is not the least controversial title for a father-daughter duet.

In the accompanying video, the two of them lie on a double bed: he bare-chested; she in a shirt and knickers. It was criticised for celebrating paedophilia, but Gainsbourg continues to insist that she “loves” the song and that recording it “was a most precious memory with him. There was such innocence on my side and such dignity on his side. Of course, there’s a provocation. If we were to release this today, it would be even worse, but for us it was so pure. It was just a love declaration.”

Serge used to kiss her on the lips “because he was Russian”, she says, as if this is a perfectly logical explanation. Gainsbourg felt loved by both her mother and father, but growing up with famously beautiful bohemian parents had its challenges.

“In my memory, we would wake up with an au pair and my parents would come back from nightclubs at seven, eight in the morning and go to bed,” she says. “We would wave goodbye and the au pair would take us to school.”

The au pairs were “horrible … each one worse than the other”. Birkin would interview potential candidates over the phone. On one occasion, she asked an applicant her age; the woman on the other end of the line replied that she was 19.

“So OK, she comes to Paris and they organise everything. And she was 90, not 19.” Gainsbourg laughs. “Those were the kind of accidents.”

Gainsbourg describes herself as a secretive child. She maintains a sense of enigma, even to her closest family. In a recent interview, Birkin said of her daughter: “She has such mystery, so you never tire of her.”

“I was maybe just growing up and being in the public eye,” she says when I ask where the mystery comes from. “I made an armour and protected myself the only way I could. I had a lot of pleasure doing the films and doing the music I did with my father. It was just the media, the interviews, the pictures at the time that were a nightmare. I wanted to go on and have a life in school and be as normal as I could. But it meant I had to deal with people looking at me. So I put up a shield.”

She actively wanted to be sent to boarding school, and tells me almost in passing that she insisted on changing schools every year.

“I didn’t have any friends,” she says. “Or rather I had friends for a year. I wasn’t closed and miserable, not at all. I found friends, but then I needed to do a film in the summer and escape and go somewhere else.”

She appeared in her first film aged 13, alongside Catherine Deneuve in the French romance Paroles et musique in 1984. Two years later, she won a César award (the French equivalent of a Bafta) for most promising actress for her role in L’effrontée. Her first English-language performance was in the 1993 adaptation of Ian McEwan’s novel The Cement Garden, in which Gainsbourg took on an incestuous brother-sister storyline. Like her father, she seems at her most comfortable when pushing boundaries. This may be why she likes working with the Danish arch provocateur von Trier, and why she’s still so in demand as an actress. She’s in The Snowman, a thriller based on the Jo Nesbo novel starring Michael Fassbender that was released last month, and has just finished filming La Promesse de l’aube, an adaptation of a memoir by the French writer Romain Gary.

Throughout her life, films have provided Gainsbourg with a sort of security. “I had real relationships with adults during the shoots,” she recalls of her teenage roles. “And that was sort of a second family, that was important.” When I ask her to describe the most “normal” days of her childhood, she immediately picks the holidays they spent together as a family. In most people’s lives, holidays are the antidote to the mundane, but I get the impression that Gainsbourg needed to get out of the bubble of Paris — away from the noise of fame and all the competing demands for her parents’ attention — in order to feel she truly had them to herself.

Serge was scared of flying, so every summer the family would hole up in a cottage in Normandy. Gainsbourg remembers playing chess with her father and cards with her mother.

“And, of course, they liked to have fun, so in the evenings we went to Club 13 [a local hotel and bar] and all the adults would skinny-dip in the pool at midnight.”

The two sisters would sit in the private screening room watching Deneuve films, occasionally popping their heads out to see “all the adults swimming naked and my father, naked, playing the piano”.

Her parents split up in 1980, when she was nine. After that, she divided her time between them. Birkin would cook her roast dinners; Serge would have her at the weekends, “so I had the best of both”.

As someone who is half British yet seems to embody quintessential Parisian cool, what does Gainsbourg make of the slew of books over recent years that claim that French women never get fat, have better-behaved children or are somehow more chic than the rest of us? Is it true?

With Kate, who died from a fall from her Paris apartment in 2013 – VANTAGE NEWS

“No. It’s very clichéd to believe that the French are so chic,” she laughs. “It’s true that the French care less, or pretend to care less. When you’re French, you don’t say you go to the gym. You go to the gym, but you pretend you drink a lot and that you never go to the gym.”

Despite her English heritage (her maternal grandmother was the actress Judy Campbell, a famed beauty and Noël Coward’s muse), she no longer feels she understands the country. Brexit makes her “so sad”, she says. “I don’t feel at home [in London]. Today, I feel that I don’t understand the English any more, I don’t know what they want.”

By contrast, Gainsbourg seems to be edging towards a greater understanding of herself. The new album is her most personal yet, and she no longer experiences crippling stage fright. “I’m able to be myself a little bit more,” she says. “And I trust that people are coming [to my performances] because they know who I am. That they’re not expecting Beyoncé.”

There’s a strange sadness that comes with being 46, the age her sister was when she died. On the album, Gainsbourg sings about the pain of knowing they’ll never grow old together, and today she describes Kate as “my protector. I was always considered the weak one or the fragile one. And she was my older sister, so she protected me. All her life, she protected me.”

Gainsbourg recounts an episode from a decade ago, when she had what seemed to be a minor water-skiing accident. Six months later, after attending a gala screening in Venice, she experienced a week-long headache. It was Kate who insisted she go to the doctor and get it checked out. An MRI scan revealed a cerebral haemorrhage and she was rushed to a Paris hospital for surgery. She survived — but had Kate not intervened, she might not have.

Gainsbourg struggled to recover from the experience on her return home. “The whole flat was covered with white flowers from people very sweetly saying ‘Welcome back’. It was like going to my own funeral. It was horrible. And then I was scared of everything.”

She still holds a conflicted attitude towards death. With her father gone, and then her sister, she can’t help but wish she had faith in God and an afterlife. “I want to believe in their spirits,” she says.

She looks down at her hands, at the teacup, at the trestle table casting its gridlike shadow across the ground. And it seems at once both completely understandable and completely unbearable that she wants to believe she might meet them again, these twin souls who taught her so much.

Rest by Charlotte Gainsbourg is released on Friday